The Psychology Of Values

Understanding the nature and influence of values on your life is non-negotiable

It is not possible for a human being to live without values.

Almost every aspect of our lives is either directly influenced by our values, or related to our values in some way.

All of our actions, decisions, beliefs, judgments, preferences, personality, and self-conception depend upon our values, at least to some extent.

And yet, some people think that values are not real or objective.

The philosopher J.L. Mackie famously begins his book Ethics: Inventing Right and Wrong, with the following quote:

“There are no objective values … The claim that values are not objective, are not part of the fabric of the world, is meant to include not only moral goodness, which might be most naturally equated with moral value, but also other things that could be more loosely called moral values or disvalues— rightness and wrongness, duty, obligation, an action's being rotten and contemptible, and so on. It also includes non-moral values, notably aesthetic ones, beauty and various kinds of artistic merit”

Mackie thought that all values are merely subjective projections onto the world.

Like colors, values are not really out there in nature, but are the product of human subjective responses to external reality.

Mackie’s influential theory, which has since been dubbed “error-theory”, is a fascinating and sophisticated philosophical position.

It could very well be true.

But the question I am interested in is this:

Does it matter?

Consider the following fact.

Every night, when Mackie would turn the lights out in his Oxford University office and commute home to his wife and children, he thought, felt, and chose in accordance with his values. Every time he went out to a restaurant, bought a shirt, or went to the cinema, he thought, felt, and chose in accordance with his values.

Whether he liked it or not, Mackie valued certain things over others.

While I did not know Professor Mackie personally, I imagine that he valued education, freedom, equality, and a handful of other things you would expect to be valued by an academic who fought for the Allies in the Second World War.

I don’t make this point to try and refute Mackie’s theory, or to show him to be a hypocrite. In fact, I think Mackie would completely agree with me in saying that he did value things even though he thought they were not objectively valuable.

I make this point to show that, regardless of whether values are objective or not, we are all forced, because we are human beings, to live our lives in accordance with some set of values.

And how you choose to live your life matters.

It might not matter from the point of view of the universe, but it matters to you.

It matters to you what your values are.

It matters to you how you uphold them (or fail to).

There are very few things that matter more for how your life turns out than what you value.

And while you don’t get to choose whether you have values (you do whether you realize it or not), you do get to choose which values you have and how important they are to you.

Whether you value status, money, and fame, or peace, security, and wisdom, it is up to you to figure it out.

The thing is, if you don’t figure it out, then someone else will choose your values for you.

No one wants this for themselves.

So if you want to learn what values are, how they impact your life, and how to figure out what values you are living by, keep reading.

What Is Value?

There is an entire branch of philosophy dedicated to the study of values. It is called Axiology (axia in Ancient Greek means “value”, “merit”, “worth", or “price”) and it has been around for over 2,500 years.

It turns out that the nature, status, and justification of value is an incredibly complex topic.

Much ink has been spilled over the concept of value, but we don’t need to get into the details of the various academic debates here. Since the point of this article is to help you begin thinking about your own values to live by, a simple introduction will suffice.

Let’s start with the concept of value itself before moving on to related concepts such as values, and evaluations.

The basic concept of value is incredibly important to human thought.

It appears in philosophy, religion, mathematics, economics, music, marketing, and many other areas.

One could reasonably say that the concept of value is a fundamental human concept.

But what is it?

I suspect that many people know how to use the concept, but would not be able to say what is meant by it.

At the most basic level, the concept of value means the measure or worth of something. This makes sense if we think as something being “invaluable”, “priceless”, or infinitely valuable. It literally cannot be measured (unless you think we can measure infinities — I don’t know enough about advanced mathematics to weigh in on how that works).

There are many kinds of value.

It will be helpful to briefly touch on some of them to see what they have in common.

In mathematics, value typically refers to a definite entity that can be manipulated according to the rules of a mathematical system.

Value is the raw material of math.

Numbers have value — numerical value.

A number is an abstract mathematical object that is used to count or measure. In short, it is a kind of value.

What about zero? Does zero have value?

The history of the number zero is quite complex and controversial. Zero is generally considered a number today, but it definitely does not have value — it is the absence of value.

In Logic, truth is often said to have value.

The “truth-value” of a statement is a value that indicates its relation to truth or falsity.

For example, if I say that “It is raining outside” when it is raining outside, then the truth-value of my statement is true because it belongs to the set of true statements.

“The truth”, on this way of thinking, is the collection of all the true statements in the world.

In economics, there is another kind of value: economic value.

This is a measure of the benefit provided by a good or serviced. Simplistically, economic value is measured through currency, but the relationship between the two can be very complex.

So, value is the worth of something, it’s measure.

If value is the worth of a thing, then what are values?

What Are Values?

It is common to distinguish between value (singular) and values (plural).

While value refers to the worth of a thing, values are things that have worth, significance, or measure.

The word “values” typically refers to abstract ideals that individuals or groups believe to be valuable.

For example:

Survival

Security

Freedom

Power

Wealth

Status

Achievement

Justice

Kindness

These are just a few examples of values that typically influence a human beings thoughts, feelings, motivations, and actions.

While the concept of values has been studied in various fields such as philosophy, anthropology, sociology, economics, one of the most useful ways of thinking about values comes from psychology.

The Psychology Of Values

In the 20th century, several psychologists developed a handful of incredibly influential and useful theories that helped make values more concrete by situating them within the psychology of real people.1

Instead of approaching values as abstract philosophical ideals, social psychologists were interested in the ways that values show up in the thinking and behavior of individuals.

In 1931, Philip E. Vernon and Gordon Allport developed the first psychological theory of values.

Vernon and Allport proposed that values are fundamentally tied to someone’s personality. They argued that in order to fully grasp someone’s personality as a totality, it is necessary to understand how their values fit together with their thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Vernon and Allport treated values as the fundamental convictions about what is and is not important in life.

They thought values were so important to a person that they helped explained not only what motivates certain behaviors, but also how someone perceives and receives information in the world.

Following the work of Vernon and Allport, two other prominent psychologists developed theories that deepened our understanding of the connection between values and the self.

The first was a psychologist named Milton Rokeach.

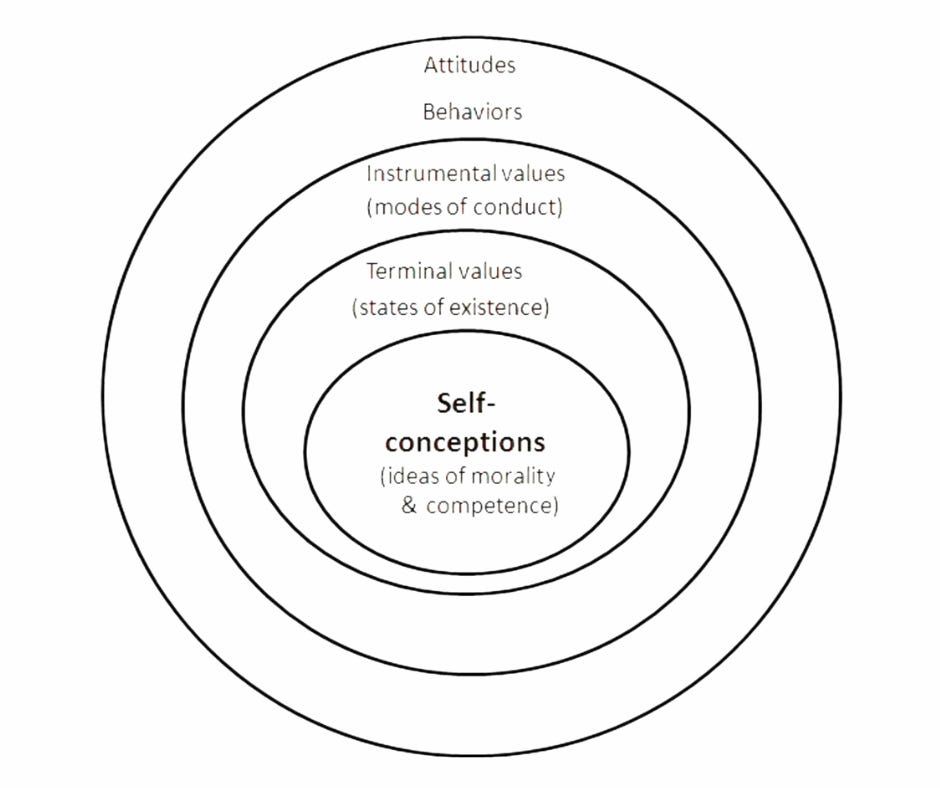

Rokeach thought that personality can be understood as consisting of a concentric system in which self-beliefs and values formed the center. At the core of your personality are your self-conception and your values. As you move outwards, your beliefs become less central to who you are and involve attitudes about other people, events, and the world at large.

Rokeach specifically defined values as:

“enduring beliefs that a specific mode of conduct or end state of existence is personally or socially preferably to an opposite or converse mode of conduct or end state of existence”

Rokeach, The Nature Of Human Values, 1973

In between the outer ring and the center are two kinds of values, which Rokeach calls terminal values and instrumental values.

Rokeach believed that all human beings share the same set of 36 universal values, 18 of which are terminal and 18 of which are instrumental. What separated people wasn’t which values they held, but their importance in someone’s personal belief system. Rokeach thought that the hierarchy of values unique to each person is what largely made them who they are.

For Rokeach, terminal values referred to desirable end-states of existence such as familial security, world peace, freedom, self-respect, contentment, and so on. Meanwhile, instrumental values referred to a person’s preferred modes of behaving and acting in order to pursue and realize their terminal values. Some examples include cleanliness, hard work, open-mindedness, honesty, and courage.

So, Rokeach thought of personality as a concentric belief system in which values are at the center.

Rokeach’s work was groundbreaking and would go on to influence future psychologists who were interested in values.

The final figure I want to look at is Shalom Schwartz, who was famous for adapting and refining Rokeach’s approach to personal values and the self.

Schwartz’s theory is the most influential and widely used psychological theories of value in contemporary research.

Schwartz defined values as:

“Trans-situational goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in the life of a person or other social entity”

Schwartz, 1994, “Are There Universal Aspects in the Structure and Contents of Human Values?”

Schwartz thought that values as defined above had seven features:

Values are beliefs linked to emotions

Values are beliefs about desirable goals or end-states that motivate action

Values transcend specific actions and situations and change in importance depending on their relevance to a context

Values are standards for evaluating actions, people, and events

Values for a relatively stable hierarchical system ordered by relative importance

Values unconsciously impact our daily lives, but can become conscious through reflection

Values compete with one another for relative importance and often require trade-offs

While I can’t fully explain each feature outlined above, I did want to highlight a key point about what Schwartz’s theory has in common with its predecessors.

The important point is that all of the psychologists I have discussed in this article have treated values as beliefs.

The reason this is important is that beliefs are mental representations that we have the ability to change.

Out of all the things within your control as a human being, what you believe is the single greatest determining factor for how your life turns out.

Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Stoicism, Marxism, and every major philosophical or religious belief system ever developed in human history are founded upon a common assumption:

You can change what you believe.

If you can change what you believe, and values are beliefs, then you can change your values.

But before you can do that, you need to figure out what your values even are.

How To Figure Out Your Values

Since values are so central to who you are as a person, it follows that if you can change your values, you can change who you are and what you do.

But in order to be able to change your values, you need to know what values you currently hold.

How do you figure out what your values are?

It is easy to recommend that you take an online quiz, complete out a survey, or series of writing prompts.

These are all useful in their own way.

But sometimes these approaches are too comfortable, too easy, and can leave us simply feeling good about ourselves for “discovering” that we value justice or caring for others in some abstract way.

Did you really need to discover that?

The #1 thing you can do to figure out what you value is to look honestly at the following two things:

What you actually do with your time in a normal day

How you spend your money every month

Remember when Schwartz said that one of the features of values was that they can impact our daily lives whether we are aware of it or not?

Well, if you don’t have a realistic idea of all of the things you actually do in a normal day and how you are spending your money, then you probably don’t understand what values are actually influencing your thoughts, feelings, and actions on a daily basis.

Values are not just abstract ideals that we think about in order to make us feel good, they are concretely realized and embodied ways of being that we either do or don’t.

So if you want to figure out what your values are, you need to look at your actions.

The interesting thing about actions is that they not only tell us what our values are, but also allow us to change them.

If you start changing your actions, then, either one of two things will happen:

Either you will change your values and become a different person, or you will become more aligned with the values you already hold.

Not everyone needs to change their values.

For some people, they already have a strong value system that serves them well, but they may be failing to fully live up to it as much as they would like.

For others, their actions, habits, and behaviors have allowed for negative values to gain a foothold in their life over the years at the expense of themselves, their bank account, and their relationships.

In these cases, it is important to honestly analyze one’s values and identify what should stay and what should go.

No one can do this for you.

But I hope that this article has given you some ways to think more clearly about the nature of values, the role that they play in shaping your life, and how you can begin to take back control of them.

Whether they help you or harm you is in your hands.

-Paul

Much of this section draws on Steinart’s 2023 book, Interdisciplinary Value Theory.

Appreciate how you’ve grounded this conversation in both philosophy and psychology. I share your view that, objective or not, values are unavoidable, and the real work is in becoming conscious of them and deciding which ones deserve to guide us.

I’ve come to see values as tools we choose and refine over time, shaped by both our nature and environment, but ultimately curated by our agency. The clarity that comes from aligning actions, habits, and choices with consciously chosen values has been transformative for me, especially in periods of transition.

I’ve explored some of these intersections between belief, agency, and lived practice in my writing, for anyone curious. But mostly, I want to say: you’ve put into words why this work matters so much.

Great read as always, Paul. However, it left me wondering: how would you factor in the attention-hijacking capacity of our current technology (e.g. social media, games, advertising…)?

Even if we assume that, ultimately, it’s down to us to let negative values in or not, it doesn’t seem fair to blame the individual for not being able to resist the barrage of psychological tricks, dark patterns, etc. that are constantly thrown at us?

For instance, I’ve heard countless friends and acquaintances use a variation of this phrase: “I went into <any social media platform> and before I realized it two hours had passed.” It seems like they didn’t value that time that they spent there (even if they value the platforms themselves), and yet they recurrently do it. How can you value something that makes you do something you don’t find valuable? Or maybe they secretly and/or subconsciously do?

I know that’s a rabbit hole, but my question essentially is if it’s a matter of having let negative values enter our lives, or having our good values conditioned or taken hostage in our current society, at least sometimes.

And then… is it possible to hold on to your values even if you momentarily drop them? If I am aware of how I spend my money and my time, and try to change that to better align with my values but sometimes still fall into old patterns, are those conflicting values? And, more importantly, can they coexist?

If I value knowledge (which is why I read you and tens of other people that post things I find valuable), but at the end of the day feel depleted and just want to watch an episode of a TV series, I guess we could say that I also value something else (entertainment, rest?), but it still seems to go against my knowledge value, because I could be putting that time towards more edifying activities.